El rescate de la memoria y la formación de la identidad

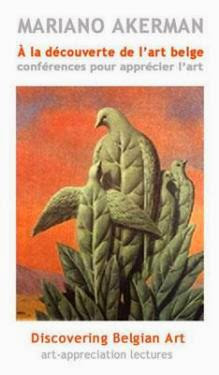

Seminario por Mariano Akerman

Centro de Estudios Bíblicos

Río de Janeiro, Brasil

Septiembre-Octubre de 2014

1. Texto sagrado y arte hebreo

2 de septiembre

2. Jaque a la reina: Ecclesia, Synagoga y la Reina del Shabat

9 de septiembre

3. Un tiempo para todo: alegorías de la fe en el arte europeo

21 de octubre

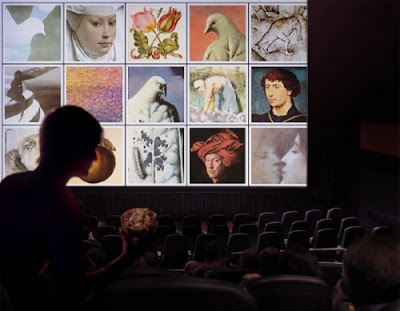

• Acompañadas por imágenes, las disertaciones son presentadas en portugués.

1. Texto sagrado y arte hebreo

No harás para ti escultura ni imagen alguna...

– Éxodo 20:4

Aborda la relación entre texto sagrado e imagen visual, subrayando la dimensión conceptual y simbólica del arte hebreo. Considera el episodio bíblico de becerro de oro y su iconografía para evaluar luego sus implicancias a la luz del Otorgamiento de la Ley. Explora las premisas divinas delineadas para la creación del Tabernáculo, el Arca de la Alianza y el Pectoral del Sumo Sacerdote de Israel. Analiza el carácter funcional, simbólico y artístico del arte hebreo. Establece una diferenciación entre "arte judío" y "experiencia judía con las artes visuales", demostrando que el alcance de la primera expresión resulta limitado, mientras que la segunda es preferible dado que ensancha los horizontes en la apreciación de las diversas expresiones artísticas dado que incluye la dialéctica intercultural.

Jaque a la reina: Ecclesia, Synagoga y la Reina del Shabat

Sólo se ve bien con el corazón,

lo esencial es invisible a los ojos.

– Antoine de Saint-Éxupéry

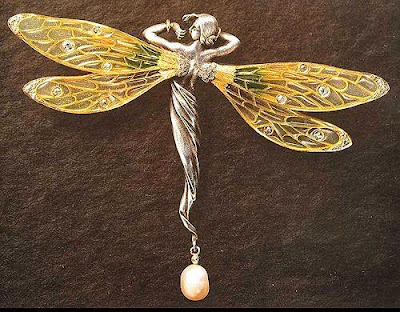

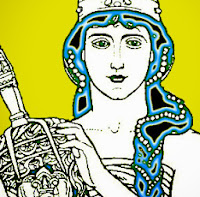

Estudia la razón de ser del par medieval de alegorías eclesiásticas al que se conoce en latín como Ecclesia et Synagoga. Explora los rasgos y atributos de cada una de ellas, así como también las correspondencias simbólicas otrora establecidas entre su forma y significado. Indaga sobre el significado de la presencia de Synagoga en el arte eclesiástico medieval y su transformación e implicancias tanto en el Majzor Leví como en la imaginería modernista de Ephraim Moses Lilien.

3. Alegorías de la fe en arte visual europeo

Pueblo lleno de fe, mas falto de luz

– Federico García Lorca

Empleadas desde la Antigüedad, las alegorías son figuras retóricas que pertenecen al campo de la ficción, pero son también alusivas y poseen atributos que las caracterizan, dándoles significado a las mismas. Habitualmente las alegorías presentan forma humana y son empleadas para transmitir conceptos abstractos. Existen así alegorías que personifican las nociones de justicia, amor, fe, y otras.

A través de su disertación, Mariano Akerman explora los orígenes, naturaleza e implicancias de diversas alegorías relativas a la fe y que fueron expresadas en el arte cristiano entre los siglos XIII y XX.

El autor examina el par teológico conocido como Ecclesia et Synagoga (1250), así como también aquél que figura en La fuente de la Gracia (1450), pintura que tiene por objeto el reafirmar la fe del creyente cristiano en los dogmas de la Eucaristía y la Transubstanciación, los que a su vez se conjugan en la tabla con una supuesta condición ruinosa del judaísmo (tanto pasado como contemporáneo), para instilar la Teoría del Reemplazo y disuadir mediante ella al converso en apariencia de su posible criptojudaísmo.

Considera seguidamente otras alegorías teológicas de la fe cristiana, especialmente aquellas que son católicas y pertenecen a la tradición española. Según Akerman, estas últimas tienen su origen último en alegorías antiguas y medievales: Fides, Justitia y Ecclesia, pero presentan asimismo una singularidad que brilla por su ausencia en el resto de sus homólogas europeas.

Akerman finalmente explora las alegorías del madrileño Monumento del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús (1914-65) y establece entonces una inesperada relación entre una de ellas y su predecesora visual, cuya naturaleza –indudablemente– es también teológica.

A través de su disertación, Mariano Akerman explora los orígenes, naturaleza e implicancias de diversas alegorías relativas a la fe y que fueron expresadas en el arte cristiano entre los siglos XIII y XX.

El autor examina el par teológico conocido como Ecclesia et Synagoga (1250), así como también aquél que figura en La fuente de la Gracia (1450), pintura que tiene por objeto el reafirmar la fe del creyente cristiano en los dogmas de la Eucaristía y la Transubstanciación, los que a su vez se conjugan en la tabla con una supuesta condición ruinosa del judaísmo (tanto pasado como contemporáneo), para instilar la Teoría del Reemplazo y disuadir mediante ella al converso en apariencia de su posible criptojudaísmo.

Considera seguidamente otras alegorías teológicas de la fe cristiana, especialmente aquellas que son católicas y pertenecen a la tradición española. Según Akerman, estas últimas tienen su origen último en alegorías antiguas y medievales: Fides, Justitia y Ecclesia, pero presentan asimismo una singularidad que brilla por su ausencia en el resto de sus homólogas europeas.

Akerman finalmente explora las alegorías del madrileño Monumento del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús (1914-65) y establece entonces una inesperada relación entre una de ellas y su predecesora visual, cuya naturaleza –indudablemente– es también teológica.

Un tiempo para todo

por Mariano Akerman.

Un tiempo para todo concierne las nociones del rescate de la memoria y la formulación de la identidad.

Hay un tiempo para todo bajo el cielo.

un tiempo para callarse y un tiempo para hablar.

un tiempo para colocar una venda sobre los ojos del prójimo

y un tiempo para colocarla sobre nuestros propios ojos.

un tiempo para señalar la ceguera del vecino

y un tiempo para reconocer la ceguera propria.

un tiempo para fabricar estereotipos

y un tiempo para deconstruirlos.

un tiempo para la manipulación y el delirio colectivo

y un tiempo para el sentido común y la integridad.

un tiempo para insistir sobre las diferencias

y un tiempo para percibir las semejanzas.

un tiempo para alejarse

y un tiempo para reconciliarse.

Synclesia, 5775/2014.

Alegorias da fé na arte visual européia

Utilizadas desde a antiguidade, as alegorias são figuras retóricas que pertencem ao campo da ficção, mas de forma alusiva; em geral, também, estão providas de atributos significativos. Basicamente, as alegorias transmitem conceitos abstratos, personificando a justiça, o amor, e a fé, entre outros.

Através de sua apresentação, Mariano Akerman explora a origem, a natureza e as implicações de algumas alegorias da fé que encontraram expressão na arte cristã a partir do século XIII para o século XX.

O autor examina o par teológico conhecido como Ecclesia et Sinagoga (1250), também aquele representado na Fonte da Graça (1450), e diversas alegorias teológicas da fé, particularmente aquelas que são católicas e pertencem à tradição espanhola. Segundo Akerman, estas últimas têm suas origens em alegorias antigas e medievais: Fides, Justitia e Ecclesia, mas as alegorias espanholas apresentam uma particularidade que brilha pela sua ausência em suas homólogas européias.

Akerman finalmente examina as alegorias do Monumento do Sagrado Coração de Jesus em Madri (1914-1965) e estabelece uma ligação inesperada entre uma dessas alegorias e sua predecessora visual, cuja natureza –sem dúvida– é também puramente teológica.

Um tempo para tudo

Há um tempo para tudo debaixo do céu.

um tempo de calar-se e um tempo de falar.

um tempo para colocar uma venda sobre os olhos do próximo

e um tempo para colocar a venda nos nossos próprios olhos.

um tempo para insistir sobre a cegueira do vizinho

e um tempo para reconhecer a cegueira própria.

um tempo para construir estereótipos

e um tempo para desconstruí-los.

um tempo para a manipulação e o delírio coletivo

e um tempo para o bom senso e a integridade.

um tempo para insistir sobre as diferenças

e um tempo para perceber as semelhanças.

um tempo de se afastar

e um tempo de reconciliar-se.

Acerca del presente trabajo

Investigación, comentario y diseño gráfico computarizado de Mariano Akerman

Recursos

• Ecclesia et Synagoga

• Las alegorías teológicas y sus atributos

• El Prado desaforado

• La llave del enigma

• Cantar de los Cantares

• Blindfold Collection

• Venda y ojos cubiertos

• Monumento al Sagrado Corazón de Jesús

• John M. Bugge, Virginitas: An Essay in the History of a Medieval Idea, International Archives of the History of Ideas 17, The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1975, ch. III: Sponsa Christi, pp. 59-66.

• Bezalel Narkiss y Aliza Cohen-Mushlin, The Illumination of the Worms Mahzor: Description and Iconographical Study, 1985, pp. 79-89.

• Bartal, Ruth. "Medieval Images of Sacred Love: Jewish and Christian Perceptions," Assaph: Studies in Art History 2 (1996), 93-110; pdf.

• Sarit Shalev-Eyni, “Iconography of Love: Illustrations of Bride and Bridegroom in Ashkenazi Prayerbooks of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Century,” Studies in Iconography 26, 2005, pp. 27-57.

• Simon Holloway, On Crowns and Pointy Hats, Davar Akher, Sydney, 1.1.2007

• Robert Michael, A History of Catholic Antisemitism: The Dark Side of the Church, Palgrave Macmillan, 2008, ch. 4: Medieval Deterioration.

• Brooke Falk Permenter, "To See or Not to See in the Middle Ages: Blind Jews in Christian Eyes", Hugh Vagantes Medieval Conference, 2010 (Medievalists).

• Katrin Kogman-Appel, A Mahzor from Worms: Art and Religion in a Medieval Jewish Community, Harvard UP, 2012.

• Laura Suzanne Lieber, A Vocabulary of Desire: The Song of Songs in the Early Synagogue, Leiden: Brill, 2014.

Ref. Educación | Disertaciones | Estudios Bíblicos | Historia del Arte